This article is a preview from the Spring 2015 edition of New Humanist. You can find out more and subscribe here.

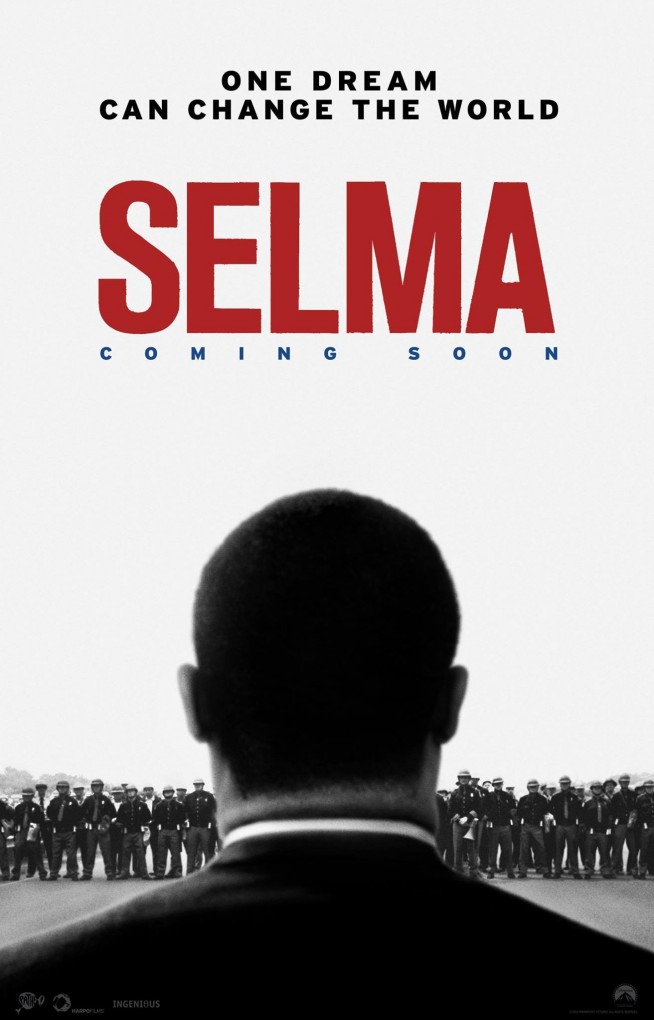

At a London screening of director Ava DuVernay’s latest film, Selma, a diverse crowd is enthralled with excitement. This is the first movie with Martin Luther King as the protagonist.

The film chronicles the three historic Selma to Montgomery marches, led by Martin Luther King, James Bevel and Hosea Williams. At the time, African Americans were allowed to vote, in theory. But, in practice, white officials put obstacles in their way. Three times, Martin Luther King’s marchers attempted to make the journey to Montgomery to demand their right to vote. They were beaten violently by state troopers. Some were killed. These marches led to America’s Voting Rights Act. The route of the march has since been memorialised.

Now, 50 years later, the subject matter of this film is crucial to an understanding of racial oppression. These atrocities took place less than a generation ago. But the relentless focus on US-based civil rights risks suggesting that black activists in Britain didn’t struggle too – or, worse, that they didn’t even exist. To assume that there was no civil rights movement in the UK does a disservice to our black history, leaving gaping holes where the story of progress should be.

The excitement about Selma echoes that which surrounded 2013’s 12 Years a Slave, the story of a freed slave who is kidnapped and sold. With both films, there’s a danger of a UK audience concluding that the horrors of slavery and racial segregation were limited to America. We must make sense of our own past to understand our future.

To rub salt in the wound, both films glitter with British influence, from acting talent to directing prowess. 12 Years a Slave was directed by London-born Steve McQueen, and the film’s protagonist is played by Chiwetel Ejiofor, who hails from Forest Gate. In Selma, British actor David Oyelowo gives the role of Martin Luther King a passionate stillness. Leeds-born Tom Wilkinson plays King’s greatest opponent, President Lyndon B Johnson.

Speaking to the Radio Times recently, Oyelowo recalled pitching a historical drama with a black character to a British executive. “They said if it’s not Jane Austen or Dickens, the audience don’t understand. I thought, ‘OK – you are stopping people having a context for the country they live in and you are marginalising me. I can’t live with that. So I’ve got to get out.’”

There is something terribly wrong here. British actors are taking centre stage in the US, but British stories about race and racism are nowhere to be seen. Black talent grows in Britain, but is not allowed to flourish. As with so many elements of American culture, there’s a danger of the US struggle against racism being globalised into a narrative of the struggle against racism everywhere. We have to be honest with ourselves. Our histories are similar, but they are not the same.

Just two years before the Selma to Montgomery marches, youth worker Paul Stephenson was agitating for a boycott of Bristol’s bus system after learning of an informal colour bar that prohibited the employment of black and Asian bus drivers. The company in charge of employing bus drivers, Bristol Omnibus, deferred accountability for the decision to the Transport and General Workers’ Union. A union representative at the time had insisted that black workers would take away white jobs. Despite the bus company deferring accountability, their sentiments were the same. The company’s general manager said: “You won’t get a white man in London to admit it, but which of them will join a service where they may find themselves working under a coloured foreman?”

Despite the obstacles placed in their way by officials, Stephenson and the West Indian Development Council earned the support of local students. Politicians made speeches in favour of their cause, and the local press ran sympathetic editorials. Stephenson was repeatedly ignored by the union and the bus company and endured a monstering in public statements and the press. He was called “dishonest” (a slur for which Stephenson won damages) and his activism was blamed for causing division.

The day before Martin Luther King told an audience of 250,000 that he had a dream at the march on Washington, 500 bus workers met and agreed to discontinue Bristol Omnibus Company’s unofficial colour bar. The following day, general manager Ian Patey committed to ending it for good. One day, we’ll have a British film about the Bristol bus boycott. But, as Oyelowo says, today the industry isn’t quite ready for it.