This article from the Winter 2013 issue of New Humanist magazine. You can subscribe here.

When I interviewed one of my sporting heroes, Mark Lazarus – who scored the winning goal for Queens Park Rangers in the 1967 League Cup Final – for a book on Jewish involvement in football, he surprised me by revealing that he had never played a game on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. And yet, earlier in the interview, he had referred to himself as an atheist. And then I remembered that I, too, as a young amateur footballer, had preferred not to play on that day, long after I had stopped believing in God. There is no contradiction here. Surely you can atone for your sins without bringing the supernatural into it? In a previous book, Promised Land, I connected the Exodus story to the city of Leeds’s often doomed attempts to liberate itself from bondage. “Religion?” wrote Isaac Deutscher. “I am an atheist … I am a Jew because I feel the pulse of Jewish history.” It is a history, as Simon Schama has shown, driven by social, political and ethical – as well as religious – narratives.

In a recent YouGov survey, about a third of Jews questioned said they had “no religion” but still identified themselves as Jews. As the sociologists who conducted the survey wrote: “It seems that God-belief is more central to religious identification for other religions than it is for Jews … in general, British Jews place a premium on communal belonging, albeit without an excess of piety or religiosity.”

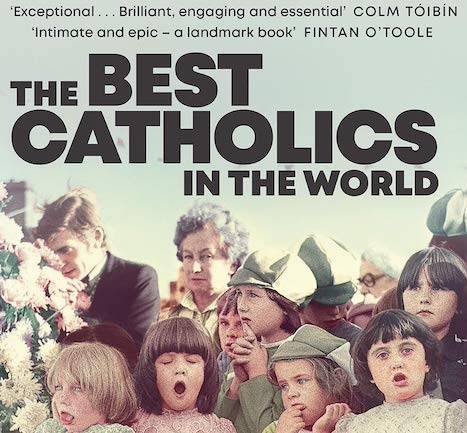

There is, historically, a good reason why Jews place such a premium: insecurity. Yet today, in Britain, the community is not only safe but thriving and vibrant and, as Judah Passow’s evocative series of black-and-white images No Place Like Home illustrates, far more of a visible presence than at any other time in its history. Go to a football match in north London, or take a walk down a high street, and you will see yarmulkes aplenty. The only quibble I have with this visually stunning snapshot of 21st-century Anglo-Jewry is that it gives – not surprisingly for a book of photographs – far too much prominence to the most visible section of the community: the excessively pious and religious. For we are about as diverse a community as you will find in Britain. And while it is true that all denominations are represented here – Orthodox, Ultra-Orthodox, Liberal, Reform and Masorti – what about the Non-Believers? Or, as Deutscher memorably called us, the “non-Jewish Jews”? True, we are less photogenic than the haredim of Gateshead or the Yeshiva students poring over a page of Talmud or the Londoners sheltering in a sukkah. However, as a Jew who neither prays nor worships, but is both fascinated and deeply moved by my religious tradition, I would like to have seen more representations of secular life.

There is always a gap between how Jews see themselves and how others see them. In his famous 1965 New Statesman essay “Am I a Jew?”, Bernard Levin argued that his lack of religious faith disqualified him from membership of the community. He was detached from Jewish life and “rejected Judaism more or less as soon as I was old enough to have any understanding of what religion was about.” And yet his journalistic big break came when a weekly periodical, trying to shed its right-wing racist reputation, offered him a job, citing his noticeably Jewish surname. In the film Annie Hall, Woody Allen imagines Diane Keaton’s anti-semitic grandmother imagining him as an extra from Fiddler on the Roof, complete with Tevye-like long beard and sidelocks.

Despite the onward march of cultural Judaism, the separatist haredim, apparently, remain the community’s visual USP. And yet Passow, an Israeli-born photojournalist, observes how “Britain’s Jewish population is now tightly woven into the national fabric.” So tightly woven, in fact, that in Ed Miliband the country might soon be heralding its first ever Jewish atheist prime minister. An interesting point that was, inevitably, lost in the row about the Daily Mail’s attack on Ralph Miliband was the academic’s debt to the “Jewish heretical” tradition of Elisha ben Abuyah, Spinoza, Heine, Freud and Einstein. Although “the man who hated Britain” was proud of his ethnicity, like many Jewish intellectuals throughout history he denied the existence of a traditional deity. Jewish humanism has had a huge, if under-studied, impact on literature, music, philosophy, art, science, architecture and comedy. During the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, and the great secular movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries – Bundism, Zionism, Yiddishism and Marxism (both the Karl and Groucho varieties) – there was an exhilarating broadening-out of Judaism, which allowed it to develop into a tradition one could embrace without religious faith.

Passow correctly asserts that, at its core, it is a Big Idea – and everything that flows from it “is just someone’s interpretation”. It has never been a dogmatic faith. Unlike Christianity and Islam, there is no creed to adhere to. Which is why we Jewish atheists, who still go to shul and refuse to play football on Yom Kippur, are able to be open about our lack of belief. We are, naturally, accused of taking a pick ’n’ mix approach to the scriptures. To this I plead guilty. When it comes to the Ten Commandments, for example, I’m a bit choosy: I’m completely against murder and theft – but not so keen on stoning adulterers and killing homosexuals.

No Place Like Home by Judah Passow is out now (Bloomsbury Continuum, £25.00)

Anthony Clavane’s Does Your Rabbi Know You’re Here? is published by Quercus