This article is a preview from the Winter 2015 edition of New Humanist. You can find out more and subscribe here.

A walk through the City of London is usually an exercise I try to avoid. Here the country’s great wealth, and indeed much of the world’s, courses through the narrow tangled streets. This is one of the last places I would expect to find an exhibition celebrating black British art.

No Colour Bar: Black British Art in Action 1960-1990 is a collaborative project between the Friends of the Huntley Archives at the London Metropolitan Archives, the Guildhall Art Gallery and the London Metropolitan Archives. This exploration of the Black Art movement from 1960 to 1990 is framed by the life works of Eric and Jessica Huntley, pioneering activists who came to the UK in the 1950s from what was then British Guyana. The Huntleys founded Bogle L’Ouverture Press, a radical publishing house, black bookshop and cultural hub. Inspired by civil rights and anti-colonial struggles raging in North America and across Africa, musicians, artists and writers in this period created a thriving black British arts scene that explored identity, place and dissent.

This important exhibition surveys the movement’s key ideas through themed sections: “Elbow Room”, “Broad Shoulders”, “Clenched Fists” and “Open Arms”. Artworks from the Black Arts Movement are juxtaposed with archival material from popular and political culture. Postcards, pamphlets, community campaign posters, private letters, books, press clippings and music punctuate each themed section, giving the visitor a real sense of how it must have felt to live through this 30-year period.

The exhibition is one you might expect to see in Brixton’s Black Cultural Archives or Hackney’s Rivington Place, places that loom large for black Londoners. Instead, No Colour Bar is located within the imposing gothic walls of the Guildhall, a 15th-century building that still forms the City of London’s administrative nerve centre. It makes for a jarring contrast between venue and subject matter. One of the Guildhall’s most infamous episodes shows how it relates the themes explored by No Colour Bar. In 1783 the first Zong massacre trial took place here. The Zong was a slave ship on which 60 people had died whilst being transported across the Atlantic. Fearing more would die, the captain decided to shackle the remaining 133 and throw them overboard. A delivered but dead slave was worthless. The cost of a slave lost at sea, could, at least, be recouped through insurance.

The trial’s presiding judge William Murray, Lord Chief Justice and Earl of Mansfield, asked incredulously:

What is this claim that human people have been thrown overboard? This is a case of chattels or goods. Blacks are goods and property; it is madness to accuse these well-serving honourable men of murder. They acted out of necessity and in the most appropriate manner for the cause ... To question the judgement of an experienced well-travelled captain held in the highest regard is one of folly, especially when talking of slaves. The case is the same as if wood had been thrown overboard.

Murray’s words tell us much about his own inhumanity but also are testament to London’s central administrative role in the transatlantic slave trade. The City financed and regulated the trade, doing so always in the interest of capital. That the No Colour Bar exhibition is held here can only be read as a quiet reckoning with this bloody history.

It is apt that the conversation between former colonial master and former colonial subject begins at the exhibition’s entrance. Two female sculptures, both the creation of Fowokan George Kelly, stand on either side of the opening. Silent yet authoritative, theirs is an announcement that this is an altogether different space from the firmly canonical grand art that sits in the upper galleries. The one on the right, named the “Lost Queen of Pernambuco”, is made in fibreglass, resin and stainless steel. She is a slender figure with a poignant and defiant gaze. Her bold, pained stare is directed towards Walter Merrett’s bust of Edward VII. On the other side of the exhibition opening is George Kelly’s “Mother of the Deep Ocean”, placed opposite another of Merrett’s works, this time of Queen Alexandra. Made from jade and copper and adorned with a thorny crown, the sculpture appears to us a figure in deep meditation. This is the Empire speaking back to reclaim its place in British history not as a separate entity but as connected and integral.

The geometric fluidity of Uzo Egonu’s painting “Stateless People: An Assembly” resonates particularly now, in the midst of Europe’s “migrant crisis”. The picture, a blend of figurative and abstract styles, is a taut construction in blues, browns, oxblood and ivory. Rounded figures are hemmed into the square frame. Disembodied yet connected, the figures appear dependent on each other for their survival. They are Empire’s capital made equally spectral and corporeal.

Security guards conducting bag checks greet you on arrival at the gallery. The irony of this now familiar ritual only hit home on my second visit to the exhibition. At this very first encounter one is reminded of crossings and borders, of surveillance and the state’s punitive might. Certain bodies, usually poor and usually black or brown, are made to navigate these thresholds with a sense of fear and trepidation. There is something of this in Egonu’s work.

A recreation of Bogle L’Ouverture’s Walter Rodney Bookshop, by curator Dr Michael McMillan and sound and visual specialists Dubmorphology, is the exhibition’s centrepiece. It is a multi-sensory, multi-media installation; a detailed honouring of Eric and Jessica Huntley’s life’s work. This hub is flanked by three walls of work from artists of the period such as Sonia Boyce and Eddie Chambers, giving us a sense of how ideas and inspiration were exchanged between the artists, publishing house and bookshop.

Winston’s Branch’s strange and compelling painting “Yellow Sky” is another that blends the figurative with the abstract. At first glance, you wonder if the stereotypically Caribbean mountains, ravine and gleaming sunlit sky aren’t in fact a rotund figure slouched against a yellow backdrop. The mind wants it to be one or the other. Branch delivers a forceful metaphor for the ways in which identity is bound up in place and locality. But the work also tells us that identity is about more than where a person is from.

Other paintings confront the banal stereotypes wreaking havoc on black lives. In Keith Piper’s “You Are Now Entering Mau Mau Country”, savage maroon heads gnash brilliantly white teeth: Victorian England’s own nightmares about the “dark continent”. On the opposite wall is Tam Joseph’s “UK School Report”, in which a cute black boy becomes an intimidating youth, and then adult gangsta. It’s a simple yet scathing comment on how, in a white-dominated society, young black men are transformed into social threats.

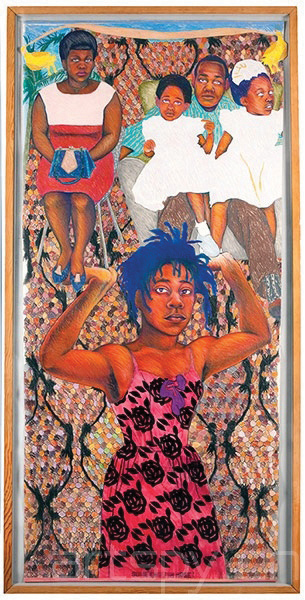

In Sonia Boyce’s famous picture “She Ain’t Holding Them Up, She’s Holding On (Some English Rose)”, a portrait of the artist stands at the foreground, almost as tall as her viewer. Surrounded by images that hint at her family and her Afro-Caribbean heritage, the figure challenges our desire to see identity as fixed. She is proudly the product of a cultural mix that is not disorderly, but coherent and fully formed.

Claudette Johnson’s “Untitled 1990” is a captivating depiction of a black woman whose body is confined by the limits of the canvas and frame, but whose self-assured expression breaks free. In the ’90s a curator told Johnson the work was too “pornographic” to be exhibited. Like many of the other works this provokes us to think about the way black bodies are politicised and policed. For a black person, to walk through the Guildhall’s space feels something like an act of resistance.

All too often in art galleries, as the artist Larry Achiampong notes, our role is as servants, as cleaning or security staff. That makes No Colour Bar an ambivalent presence. On the one hand it props up the established art world and its colonial legacy (how, to take another example, did the Tate Gallery’s founder – a sugar merchant – make his fortune?). On the other, I am grateful for the discordant presence that, for six months at least, disrupts the conventional history of art in Britain.

“No Colour Bar” is at the Guildhall Art Gallery, London, until 24 January 2016, admission free