This article is a preview from the Summer 2016 edition of New Humanist. You can find out more and subscribe here.

Many atheists accept that there are some good points about Christianity, particularly the “primitive” variety preached by Jesus and his disciples. Primitive Christianity was, it seems, all about reaching out to the weak and poor, fighting arbitrary power and prefiguring an earthly paradise of peace, solidarity and universal love. But this benign utopianism was gradually overshadowed – so the story goes – by orthodoxies, hierarchies and duties of obedience, and finally snuffed out by an arrogant, dogmatic braggart called Augustine of Hippo.

Augustine was born in North Africa (in what is now Algeria) in 354. His parents were black and they were neither rich nor sophisticated but they had ambitions for their son. He was brought up to admire the imperial state and he studied hard to achieve fluency in its language and culture, ending up, you might say, more Roman than the Romans. He became adept in rhetoric and classical philosophy, at least those parts that were available in Latin, and by his late twenties he was an acclaimed teacher in Milan. His mother was a Christian but he “insulted” her faith, dismissing it as uncouth, superstitious and “absurd”. When he reached the age of 31, however, he suddenly changed his mind. He realised that he had “jeered” at Christians for “believing things they did not actually believe” and – to the delight of his mother and the dismay of his students and colleagues – he decided to embrace Christianity.

He then returned to Africa, where he laboured for the rest of his life – he died in 430 at the age of 75 – to make the Church institutionally robust and intellectually respectable. He administered, negotiated and dispensed justice, as well as preaching thousands of sermons and writing some 80 books, culminating in the massive City of God. His obsession with the contrast between divine order and human unruliness had the effect, according to his detractors, of smothering the original vitality of Christian teaching in a narrow-minded version of Platonism. He dreamed up the doctrine of original sin and propounded a draconian series of dualisms: spirit against flesh, mind against matter, male against female, heaven against earth, eternity against temporality, and the blessed against the damned. He replaced love of the world with bitter contempt and, according to Hannah Arendt, denigrated worldly politics and the duties of responsible citizenship. Over the coming centuries, his antisocial obsession with sin was carried round the world as part of basic Christian doctrine, before leaking out to poison modern civilisation as a whole.

But there has always been another side to Augustine. Before he wrote The City of God, he produced the Confessions, in which he reflected on his life up to and including his conversion to Christianity. It is not an ordinary memoir, however. Instead of boasting about his progress towards enlightenment, Augustine spoke vividly of the vicissitudes of love, loss and mourning, at the same time as insisting that we will always be a mystery to ourselves. We live our lives in the medium of time, constantly aware of our present slipping into the past as our future enters the present – but we have no idea what time really is. “If no one asks me, I know,” he writes. “If I try to explain it, I do not.” We are conscious of obscurities that we cannot comprehend. “The mind is too narrow to contain itself,” as Augustine puts it. “I do not understand what I am.”

Augustine presented the Confessions not as reminiscences for the edification of his readers but as private prayers addressed to his God. We may be charmed, moved, or appalled by what we read, but we are aware that his back is turned and that – like Hamlet watching Claudius – we are witnessing a performance that was not meant to be

observed. We may also reflect that there is something odd about Augustine’s project of talking to God, since he cannot have believed that he was going to tell him (or her) anything that he (or she) did not already know. Augustine was aware of the problem. “Why, O God,” he writes, “why am I giving you an account of all these things?”

The question can be taken in a religious sense, in which case the answer is that he was seeking guidance or forgiveness. But there is also a question of literary form. Augustine’s address to God opened up a vantage point beyond both himself and his readers, from which he could consider matters that lie beyond the limits of human experience. “I do not know what I was talking about,” he writes. “You know, O God, but it still eludes me.” He could not find himself until he looked elsewhere, guided by God’s truth. “You then turned me towards myself,” he writes, and “set me before my own face that I might see how vile I was.”

Apart from its contribution to the development of Christian doctrine, the Confessions enacted a revolution in narrative technique – a revolution that set the narrating subject free to reflect on its own incompleteness. You could think of it as the literary equivalent of the revolution in art brought about by the discovery of perspective: God functions not as an actually existing creator and judge, but as an imaginary horizon. God in this sense is a literary device, offering new ways to arrange our perceptions and enabling us to inject some irony into our relations with ourselves (as in Augustine’s prayer: “Lord make me chaste, but not yet”) and to recognise ourselves not as isolated bastions of self-knowledge but parts of a drifting cloud of unknowing.

You do not have to be a believer to be impressed by the Confessions. Augustine’s attempts to articulate the turbulence of inner existence did not, it seems, have any precedent and they can perhaps be seen as the origin of modern subjectivity. Directly or indirectly, they inspired such secular memoirs as Rousseau’s Confessions, Wordsworth’s Prelude and Jean-Paul Sartre’s Words. The feminist novelist Rebecca West paid tribute to him in a “short biography” in 1933. Augustine was a “horrid little boy”, she thought, suffering from colonial cringe and an “unhappy attitude to sex, consisting of an exaggerated sense of its importance combined with an unreasonable horror of it”,. But he was also “one of the greatest of all writers”, cultivating “the same introspective field as the moderns”. The “subject matter” of the Confessions became the theme, West writes, of Shakespeare, Proust and Joyce. Augustine was a writer not for Christians only, but for us all.

* * *

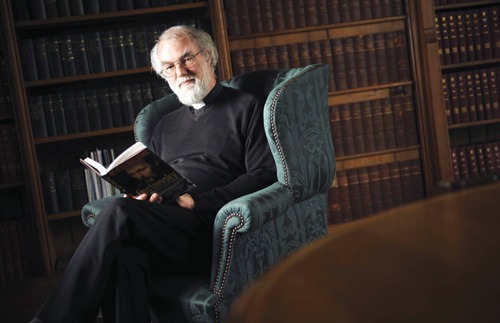

Rowan Williams is undoubtedly a Christian. As archbishop of Canterbury from 2002 to 2012, he offended some fellow Anglicans with his progressive ideas about sexuality, marriage and women bishops; but he always insisted on his commitment to the fundamentals of Christian belief, such as the reality of a loving God and the Son who died to save us all. On the other hand, he spoke about his beliefs with an open-minded curiosity and philosophical breadth that atheists found rather disarming; and his new book, On Augustine, has the same kind of charm.

If Williams is right, Augustine does not deserve his bad reputation. His arguments were sometimes hasty, unclear and conflicted but they were also inventive, exhilarating and disconcerting. He fought against the idea of religion as a lonely search for God – an idea that, Williams writes, “can lead to a self-important, individualistic religiosity that talks glibly about my spiritual journey as a thing in itself, a fascinating exercise in a specialist activity, a very elevated hobby”. For Augustine, religion was not a quest for private salvation but “the search for right living with each other” – not just those we find “agreeable” but strangers, critics, outsiders and enemies. Taken as a whole, according to Williams, Augustine’s writings demonstrate that Christianity is “something that can be thought with: not a hermetically sealed set of doctrines, but a coherent narrative of human growth”. To Augustine, of course, human growth meant “growth into divine communion”, but Williams hopes that “those who do not accept the theology will still acknowledge the sheer diagnostic skill of the phenomenology”.

On Augustine is not a book for beginners. It is based on academic papers written over the past 30 years, with Latin quotations left untranslated, and it assumes some knowledge of the Bible and of Kant, Hegel and Wittgenstein. Moreover, Williams does not shrink from the darkest thickets of traditional theology and he devotes several chapters to Augustine’s mind-boggling treatise On the Trinity. The idea that “God is three and God is one” has generated a lot of hot air over the centuries and is often dismissed as either a metaphysical fairy tale or a blatant contradiction.

With the help of Augustine, however, Williams is able to present it as a clear-eyed meditation on the complexities of love: a warning against the exaggerated devotion that leads to “the possessive immobilising of what is loved” and an elucidation of the paradox of “loving before we know, yet needing to know before we love”. As for The City of God, Williams finds that, far from diminishing the “public realm”, as Arendt supposed, it energises it: “A society incapable of giving God his due fails to give its citizens their due,” he writes, and Augustine’s recognition of the “awkwardness and provisionality” of every possible form of social organisation can open the way to an “authentically political” community. We can then return to the comparatively homely world of the Confessions and the idea of self-knowledge as requiring a “sense that the root of the matter ... is always elsewhere”. The end of certainty is the beginning of wisdom, according to Williams’s Augustine: the prospect of a final resolution will always recede as we advance towards it and, we are told, “Self-interrogation without hope of closure is how I know God.”

Williams’s lessons in vulnerability and imperfection are eloquent, illuminating and no doubt salutary. Some Christians will find that they harmonise with their beliefs; others will repudiate them as a threat to their righteous self-assurance. Non-believers, however, can endorse them wholeheartedly, not as evidence of the truth of Christian doctrine but as proof of the power of literary invention.