This article is a preview from the Winter 2016 edition of New Humanist. You can find out more and subscribe here.

I was having a saloon bar conversation about the existence of God with Stephanie Glover, an ex-student of mine from York University, when she suddenly asked if I’d ever had a “a transcendent experience”.

How did she mean?

“One of those moments when you are suddenly overcome by a sense of awe, a feeling of oneness with the universe, a glimpse of what Freud called ‘the oceanic’.”

“That’s a trick question,” I said. “If I admit to a transcendental moment, you’ll immediately suggest that it must have given me some insight into the higher meaning of life and therefore some glimpse of the divine. From there, for a paid-up Christian like you, it’s a short step to Jesus and all his works. If, however, I insist that I’ve never had any such experience then you are going to say that I lack imaginative powers, that I am a vulgar insensitive materialist.”

“Same old Professor Taylor,” said Stephanie with a weariness of tone that I remembered from our postgraduate seminars on structuralism. “Why answer a direct question when you can invoke a conceptual distinction?”

On the bus home I pondered my cowardice. Why hadn’t I chosen to mention the one attempt I’d made to reach what Stephanie would call a higher level of consciousness?

I could have told her about how, back in the late 1970s, during my time in York, I’d fallen in with a young woman called Sara who liked to describe herself as a pantheist. She was mostly an amiable companion but as soon as she found herself in anything resembling nature she would start quoting Wordsworth. “The lake, the bay, the waterfall, and thee the spirit of them all,” she’d recite as we made our way back home through Rowntree Park.

“I feel a presence that disturbs me with the joy of elevated thoughts,” she’d say as the moon rose over Derwent College residential block.

It must have been my surly reaction to this immanent chatter that led Sara to propose an LSD trip in Scarborough. If I booked the hotel she’d buy the magic pills and we could expand our consciousness together.

So it was that one sunny morning in June we sat on the beach and proceeded to swallow the magic potions. Half an hour later the bad times arrived. Sara drew my attention to the incoming tide. “Look at the pattern of the waves,” she whispered. “Can you hear the sound as the tide withdraws? It’s so like that poem by Matthew Arnold, ‘Dover Beach’. ‘The grating roar of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling at their return up the high strand’.”

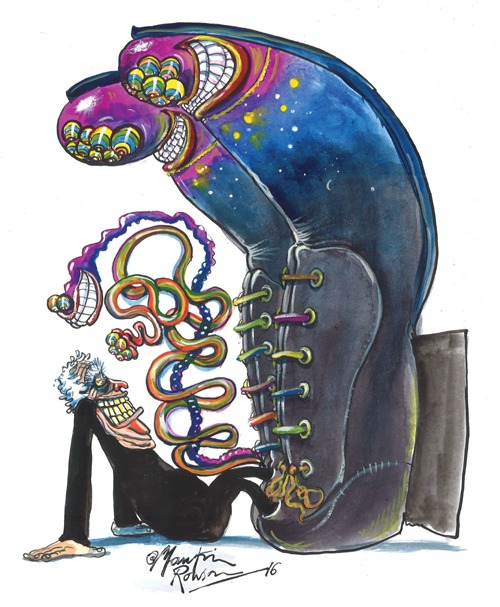

I could neither see nor hear anything of the sort. Instead I became solely preoccupied with my shoes. Why, I fretted, had I chosen to wear such a good pair when there was a danger that they might be spoiled by the sand and the sea? And why hadn’t I replaced the lace in the right-hand shoe which now showed every sign of breaking? Perhaps I should buy a reserve pair of laces. But where in Scarborough might I find a shoelace shop? And even if I did find one what were the chances of the shop having a long enough pair of laces to fit these particular shoes?

And so it was that, even as Sara drew my attention to the possibility of seeing the world in a grain of sand and a heaven in a wild flower, I insisted that we immediately make for the High Street where I distinctly remembered a branch of Clarks that might or might not sell shoelaces.

Nothing that Sara said from then on could wean me from my obsession. As she noticed the sky taking on a russet hue, I was doing up my laces in a way that minimised the strain on the lace in the right-hand shoe. And as she told me that the extraordinary difference in the texture of sky and beach was now reminding her of Louis MacNeice’s line about the “drunkenness of things being various”, I was pondering the possibility that one of the nearby amusement arcades might just be offering a pair of shoelaces as a reward on one of its gaming machines.

One week after our trip, Sara tried to explain why I’d been so immune to transcendental thoughts. “You’re terrified of encountering another reality. Terrified of anything which might disturb your rational take on the world. Terrified of letting your feet off the ground.”

“You’d have been the same if you’d only had one secure shoelace,” I protested. But she’d already stopped listening.