This article is a preview from the Spring 2018 edition of New Humanist

‘‘Thank you for letting us have sight of Winter Roses,” said the A5 notelet bearing the publisher’s imprint. “We appreciate you sending us your first novel but very much regret that at the moment we have no plans to add any new authors to our list.”

When I checked my diary, I discovered that this particular publishing house had been having a “sight” of my novel, or, as they unnecessarily insisted, my “first” novel, for the best part of six months. It had taken them all that time to come up with a response that was not only ineptly worded – why on earth couldn’t their reader have simply “seen” my novel rather than having “sight” of it? – but also contained an excuse of such lameness that one could only wonder how it hobbled its way onto the rejection slip.

I would have been altogether more relaxed about the matter if I hadn’t been counting on a positive reply. For although there is little in my existing list of sociological publications to suggest that a major work of fiction might be the logical next step in my career, I have always believed that my profound sensibilities and distinctive ear for language mean that I have rather more in common with, say, Saul Bellow or Philip Roth than with the battalion of fellow social scientists whose paradigm of written success is a five-page heavily researched article in the British Journal of Comparatively Self-evident Findings.

I have to say straightaway that this idea of myself as being both sensitive and linguistically adept is far from being self-generated. For as long as I can remember, my various romantic partners have nearly always felt the need at some point in our relationship to remark upon my literary potential. “Have you ever thought about writing a novel?” asked Pat Wilson back in the early 1970s when I had entertained her for the best part of 20 minutes with my astute portraits of our fellow diners in the Leicester Square branch of the Quality Inn.

“Why don’t you write any of this down?” Gillian Parsloe had openly wondered when I elaborated upon the manner in which the grey mercurial North Sea merged with the grey horizon, during our illicit weekend at Scarborough’s Grand Hotel in the late 1980s.

Others went further. In the late 1990s, Jenny Hodge, the successful radio documentary producer, didn’t merely suggest that I might think about a fictional future. She was sufficiently impressed by my reflections on the essential melancholy of Venice to suggest that the job was as good as done. “You know something,” she said as we sat staring across the Grand Canal from the steps of the Salute church. “You already have a novel in you.”

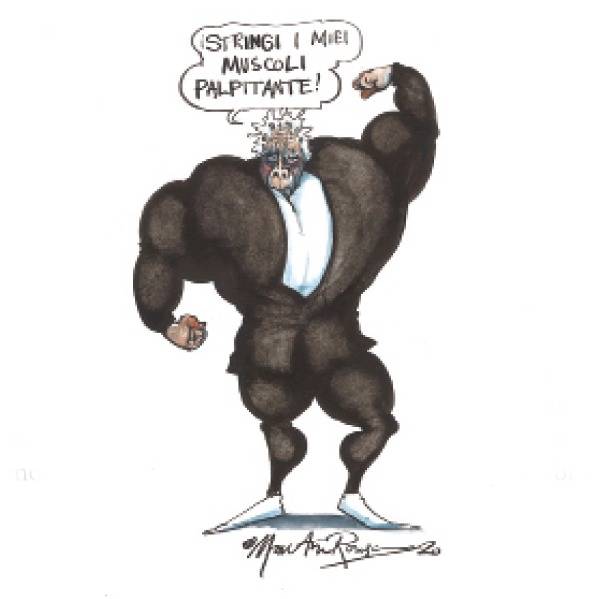

One or two of my more cynical male friends did, from time to time, suggest that I should not take these various literary testimonials too seriously. In their view, there was no easier way for a woman to flatter a middle-class male companion than by suggesting that they enjoyed literary sensibilities. It was the intellectual equivalent of marvelling at a man’s ability to unscrew the recalcitrant top off a bottle of tomato ketchup. “Gosh, aren’t you strong!”

I haven’t so far allowed such critics to know about the rejection of Winter Roses but I am already prepared to cite the stories of how Vladimir Nabokov and J. K. Rowling experienced similar setbacks, in case my present partner should ever publicly choose to use that rejection as proof of my inadequacies. “Frankly, I wasn’t the least bit surprised they turned down his silly book. When it comes to imagining another person’s point of view he enjoys rather less insight than the average paving stone.”

But as I now realise, after bumping into Jenny Hodge in a lift at Broadcasting House a fortnight ago, I don’t need to fret about my career as a major novelist. Frankly, I now have other fish to fry. “Isn’t it funny how people in lifts betray some aspect of their character even though they contrive to be so enigmatic?” I said in between floors. “When you think about it, you could call it a case of the elevator as revelator.”

As the doors slid open Jenny gave me a loving smile. “You’re a poet, but you don’t know it,” she said.