This article is a preview from the Autumn 2018 edition of New Humanist

The 1980s: the Reagan/Thatcher era of greed triumphal, when glamour replaced the grunge of politics and trade unionists were yesterday’s men. Dressing up was the new art form. Sado-masochism was the new sex. Right-wing was the new revolutionary. The bonfire of regulations freed the city boys to call the shots, and thrusting yuppies disco-danced the night away, while Aids victims were reviled and demonstrators truncheoned.

The decade broke from the post-war Keynesian consensus with a new, harsher neoliberal settlement. Today that too is broken, yet remains in place. The publication of two recent books suggests that we could learn much from that earlier moment. This is no nostalgia trip: immersion in these different yet related versions of the bling decade might show us how the 80s changed the tune and give us the courage to pull another switch ourselves.

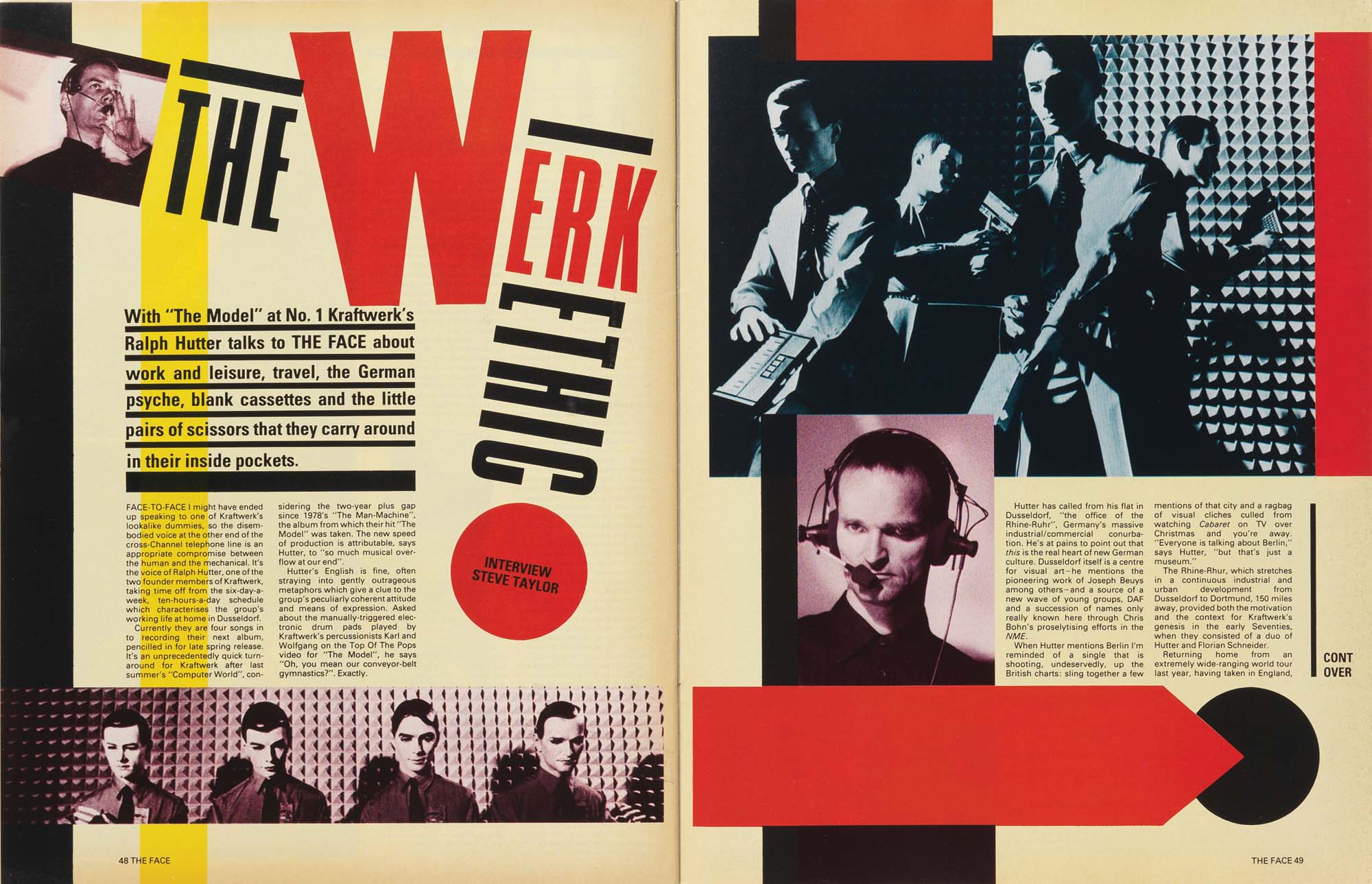

Both books deal with the world of magazines. The famous editor Tina Brown’s The Vanity Fair Diaries 1983-1992 (Weidenfeld and Nicolson) relives the turbo-charged immediacy of her stellar success as editor of the New York magazine. Meanwhile, Paul Gorman’s weighty tome, The Story of the Face: The Magazine that Changed Culture (Thames and Hudson), reproduces the revolutionary graphics and images of his subject. This is accompanied by an exhaustive, year-on-year account of the magazine’s development and production, its changes of personnel, office moves, attitudes to advertising and modes of distribution.

Magazines were still important in the 80s, before the internet came along. They defined the trends. They covered much more than style and, according to GQ editor Dylan Jones, “became the culture itself”. Gorman believes that in flattening cultural boundaries – dissolving the distinction between pop and “high culture” – they prefigured the digital space of today.

The two books are very different, yet each eventually produces a similar sensation of gluttony, of having guzzled too long on the excess of an unrelenting novelty, which eventually palls as endless consumerism.

A friend who knew Brown at St Anne’s College, Oxford, then an all-women institution, once told me that as an undergraduate the future media mogul never appeared in public without full make-up, even at breakfast. The anecdote captures a faint sense of ridicule that accompanied Brown’s early fame in London, but also hints at her perfectionism and determination. Taken seriously or not, she transformed the moribund Tatler into a sparkling, must-have style bible before Condé Nast enticed her to New York. There she revitalised another shaky publication with a long pedigree, Vanity Fair. This became a sensation, its content, style and images defining the decade.

Her diaries of those years relive a period hysterical with glamour. Brown’s stunning blonde looks must have helped, but she clearly had a genius for what she calls the “Zeitgeist”, mixing the moods of the moment into a lethal cocktail. The diary format captures the energy of the 80s and her own energy surges off the pages. “Don’t expect ruminations on the sociological fall out of trickle-down economics,” she warns. “These were years spent amid the moneyed elite of Manhattan . . . in the overheated bubble of the world’s glitziest, most glamour-focused publishing company.” And with what gusto she retells it.

* * *

Recalling those years by reading her diaries at breakneck speed I understood something that had escaped me at the time. Brown personifies the cultural change that overtook her generation. A student in the 1970s, she experienced the crumbling of social democracy in the face of ultimately unsuccessful demands for progressive economic and cultural change. Margaret Thatcher’s abrasive politics drew fierce opposition, but also opened the door to once taboo ideas of radical individualism and thrusting competition that eventually became the new normal. This made selfishness exciting by coating it in glamour.

For yes – the 1980s were all about welfare cuts, attacks on trades unions and poll tax riots. But here is the other side of it revealed: the iconoclastic glee of flouting the gentler assumptions of clapped-out compassion. No more careful spending, tasteful clothes and quiet lives. No more peace and love. It was the era when the consumer society finally arrived fully formed, without excuses or apologies.

Brown frankly acknowledges the decadence and destruction beneath the surface of this money-mad society. Yet it is this very decadence that allows her to make Vanity Fair the triumph it becomes as she exploits her readers’ craving for novelty and excitement. She understands and cunningly uses its cultural miscegenation, treating intellectuals like film stars and socialites like geniuses.

The triumph of getting a Vanity Fair cover of the Reagans dancing together sums up the attitude. Brown didn’t “much like” Reagan, but the picture spelled “pure optimism” and she admired the President’s gift for “instinctive collusion between imagery and national mood”. That was what mattered for Brown: to grab the mood, to pin down the butterfly of the moment in an image, for which she was prepared to use her talents to endorse a man whose politics she probably despised. She knows that in New York “money gets in the blood like a disease”, but also feels the unending thrill of the place, where “crassness and need” metastasise into the heady intoxication of being iconoclastic in that special way that only the really rich can be.

There were friends of Brown’s circle dying of Aids, and there were sinister tales of murder in the towers of the wealthy. Even those, though, could become part of the Vanity Fair mix, part of its seductive transgression. So the flaw was the crazed double consciousness, the disavowal that made it possible to transform the ugly and politically indefensible into aesthetic thrill.

* * *

The Face was not the British version of Vanity Fair. In some ways it could be positioned as its opposite. There were points of contact; the presence of The Face in Manhattan was in part due to James Thurman, who knew Si Newhouse, CEO of Condé Nast and thus Brown’s boss. It would oversimplify to set up a stark contrast between Manhattan glamour and the downbeat alternative eccentricity of London style in shabby 80s Britain. Both Brown and the inventor of The Face, Nick Logan, understood that the message of the new, the exciting and the shocking must be delivered through the prism of style.

However, Vanity Fair sought big names, while The Face sought the unknowns waiting to be discovered in the basement clubs of urban Britain. The Face was also the last incarnation of the avant-garde. It emerged from the defiance of punk and the music scene of the late 70s, a time when music fused with fashion and each was challenging boundaries. So it brought men’s fashion to the fore and promoted new bands, but it also featured the photography of Cindy Sherman, Robert Mapplethorpe and Bruce Weber, whose work explored taboo issues in innovative forms.

The avant-garde sensibility of The Face in the 80s (in the 1990s it became more interested in the mainstream and eventually succumbed to commercialism) was mirrored in the academic world and politics. “Transgression” was a buzzword in cultural study circles and “subversion” replaced “revolution”. Even the then Marxist theorists Stuart Hall and Martin Jacques translated the seduction of emerging forms of capitalism into the “New Times” project, launched by Marxism Today, the theoretical organ of the Communist Party. In attacking sclerotic trade unions and public services, their “project” meant to promote more radical forms of democracy, yet ended up endorsing Thatcherist assumptions. The radical chic of promoting right-wing politicians and ideas in a left-wing magazine became a self-defeating triumph of style over content.

It would be easy enough to dismiss The Face as a puerile example of style over substance. But that misses one absolutely vital point: style was the spoonful of sugar that made the medicine go down. The “great moving right show” was clad in the costumes of the latest fashion.